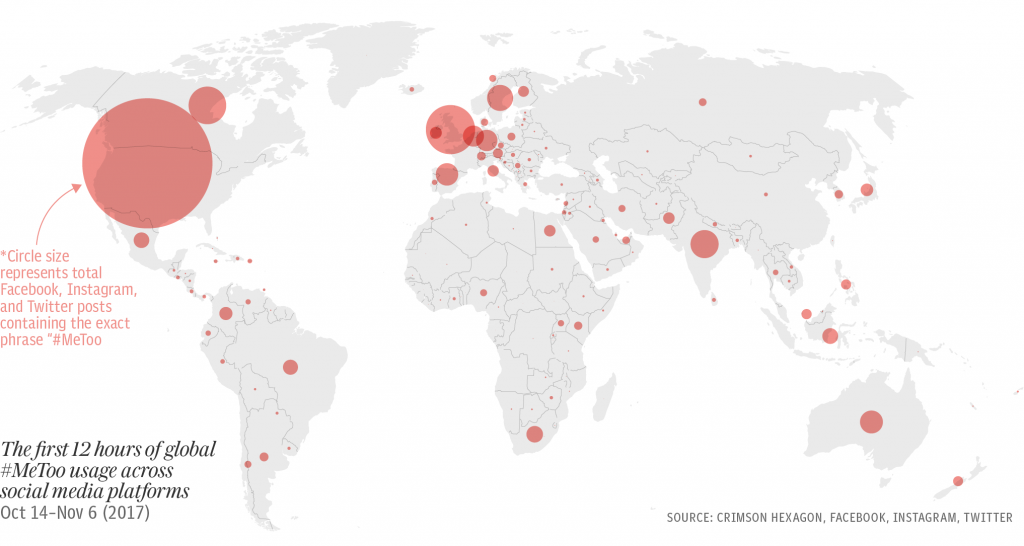

There’s no denying the two-word hashtag #MeToo and the use of the Internet renewed a widespread consciousness of feminist ideas in the public sphere, shifting the cultural outlook of associating vulnerability as a sign of oppression to strength as women took off their veil of silence. But what we didn’t know was the global impact the campaign would have, #MeToo is igniting the fight for women’s rights flaring up calls for a new social norm all over the world.

As millions of women took the streets and held rallies standing in solidarity to mark International Women’s Day, one thing is clear – the personal is political. As the movement continues to cross racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic boundaries – it’s important to take a closer look at how the movement is being translated in different parts of the world.

In South Korea, the movement has taken a surprisingly strong hold in the socially conservative nation. Much like the United States, a series of high-profile sexual assault allegations against some of South Korea’s most prominent politicians, entertainment figures, and professors have incited calls for gender equality and a new social norm. The watershed of accusations began when female public prosecutor Seo Ji Hyun accused former South Korean ministry of justice official Ahn Tae Geun of groping her during a funeral in 2010. Seo’s claim opened a flood of similar revelations, including allegations against rising political star Governor Ahn Hee-Jung of South Chungcheong province, filmmaker Kim Ki-duk, and poet Ko Un – a prominent literary figure revered as a potential Nobel Prize recipient. The unexpected rapidity of the #MeToo movement was a stark reminder that the country remains a male-dominated society with deep-rooted societal bias against women, but it’s also important to note the boiling rage of public outcry made it clear South Korea is a famously adaptable nation.

The new dynamic and momentum in the discourse surrounding women’s human rights is beginning to be reflected even on the policy level. A record number of women hold cabinet positions in South Korea. Though only 30% of President Moon Jae-In’s administration is female, it is the highest figure in South Korea’s history – no doubt, a signal towards gender parity. Clearly, there is an appetite on the global stage for leaders to apply a more gender-conscious decision in appointing key leadership positions; and in time, we will see how the gender-sensitive moves will be reflected in Korea's greater social structure.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed